The MaNeScale project is one of the so many public health projects that worked towards creating a change in the Maternal Newborn Health in Uganda. The motivation behind the design of this project was to develop an innovation that saves mothers and their newborns by strengthening the local health system using the available resources. The purpose of this innovation was to curb the unacceptable high maternal and neonatal mortality rates which accounted of 6000 maternal deaths, 32000 neonatal deaths and 39000 still births amidst the policy implementation gap in Uganda. The project was implemented in Busoga region an area that has over 4 million people which is 10% of the country’s total population. The solution presented through MaNeScale entailed the following components to improve the MNH care services in Busoga region;

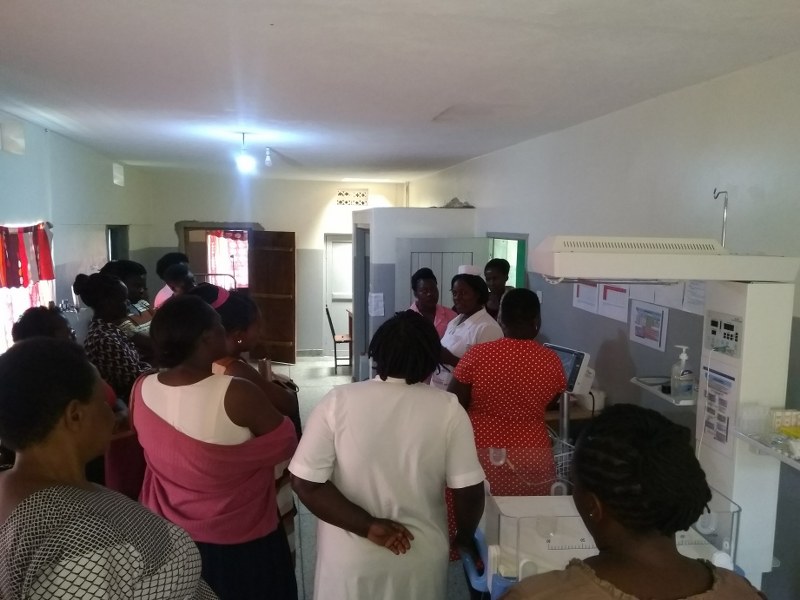

- Training and mentorships for knowledge, skills and team work which involved passing on skills to providers regarding Basic Emergency Obstetric and Newborn care and maternal and perinatal audit and later supplemented with advanced newborn care training.

- Data strengthening that focused on developing institutionalized newborn registers which were inexistent in Uganda which were strengthened through mentorship.

- Catalytic provision of key drugs, supplies and equipment for maternal and newborn care was also a great component of the project that was a one off supply to bridge gaps. Moreover, provision of these essential commodities is now done by the individual health facilities.

- Engaging leaders and developing champions was also part of the MaNeScale solution. This was done right from the beginning and was continued through feedback during mentorship, a quarterly collaborative of all health facility leaders by level, and by involving emerging good performing health workers as co-mentors. In the end, this created maternal and newborn champions across the region.

- Lastly was involving the community in various ways: 1) Mothers were involved in designing and implementing KMC; 2) In Luuka district we run a community health worker model or Village Health Team (VHTs) approach with 250 VHTs, and 3) We have on an annual basis held meetings with technical and the political leadership of the region to consult and give feedback.

MaNeScale registered a lot of positive impact and success that includes establishing neonatal units from 0% to 100% in six hospitals and six health center IVs that are all functional, 120 health provider acquired skills, over 35,000 mother and baby pairs delivered in the health facilities over the five years with improved care due to the quality improved interventions were institutionalized and overall, the maternal mortality ratio, neonatal mortality and still births significantly dropped.

One key story is how we saved a mother and her quintuplet babies by caring for them in a general hospital by only nurses and midwives, as narrated in the box below:

A mother giving birth to five babies at once on the night of August 23 and the morning of August 24 2019 was big news and it attracted hordes of people to Iganga Hospital wanting to have a glimpse of 30-year-old Safiyati Mutesi. With prior history of giving birth to twins and triplets, Safiyati did not have any complications during her pregnancy. However, trouble only arose during delivery when her first baby came out at the entrance of a health facility near her home and the postnatal bleeding at the end of her 5-baby delivery process, 40 kilometres away, in Iganga.

Although it is apparent that Safiyati delayed home, she was lucky to be in a catchment area where different studies including MaNeScale under the auspices of the Makerere University Centre of Excellence for Maternal and Newborn Health (MNCH Centre) have created a regional network of maternal and newborn care that has linked several health centre IVs and hospitals through refresher trainings on emergency obstetric care, quality improvement collaboratives and ongoing mentorship among other things.

A 2008 Nigerian study found that children born multiple births are more likely to die during the first year of life compare to children born singletons, independent of child’s sex, birth order, pregnancy care and delivery care, maternal education and nutritional status, household access to clean water and sanitation, and other factors. Safiyati’s multiple babies are not any different from the cases referred to in the above studies. While in hospital for over three weeks, medics could easily check these low birth weight babies and act if need arose. However, they are now back in the community, a totally different setting from the hospital. Continuing with Kangaroo care, maintaining hygiene and warmth, as well as infection control and proper feeding will be critical in the care of the quintuplets for better outcomes.

At discharge the MNCH Centre arranged and had two staff members from the Iganga Hospital Special Care Unit escort the family home and help set up the babies’ place of aboard. They also gave a health education talk on newborn care to the gathered community. Also, with support from the MNCH Centre, a neonatal nurse from Iganga Hospital will make a monthly visit to the family to assess the health status of the babies. According MNCH Centre’s Prof Waiswa, this will be initially done for three months. “Follow up is critical for such high-risk babies. With the support they have been getting while in hospital reduced, following them up in the community will be important.”

As of the recent visits, the babies and mother are doing well and receive support visits from the hospital providers and the Center staff.

There’s a great room for scalability because the project was designed “with an end in mind” that it can spill over to Uganda, Africa, and South Asia where the structures are similar. This innovation operationalizes the WHO Quality of Care framework for maternal, newborn and child health. The MaNeScale solution is already “self-sustaining” because of the way the project was designed and implemented. The project was embedded in existing structures, built on the strength of leadership and implemented over a long period of time. This has enabled the hospitals and the government to “buy into” and to be able to provide resources. The champions and the results “people see” have been the hallmark of sustainability. Our solution has been integrated into the community and has been adopted by UNICEF in their work other settings (Northern and Western Uganda). The socio-cultural and/or environmental factors which might help the solution to persist in time will include government prioritization and investment, continued support to hospitals and mentorship, and community demand. We are particularly concerned the lower level facilities where more support, staffing and electricity are needed. In future, we advocate for specialized neonatal nurses and doctors in these kind of settings.