By Janella Sorin Kang | I am working as an intern with the Makerere University’s COMONETH project that ultimately works towards reducing neonatal and maternal deaths in Luuka District of Eastern Uganda. COMONETH aims to design and implement a community owned but facility-linked district-wide intervention that promotes high coverage with preventive care and improves quality of clinical care equitably leading to impact on maternal, perinatal and neonatal mortality in rural Uganda. Through the home visits, the COMONETH team collects Verbal and Social Autopsies (VASA). VASA focus on asking the questions directly to the patient’s relatives and family to better understand the behavioral barriers, care seeking processes, and what disease(s) each individual had to determine the cause of death: the social determinants of maternal health and mortality.

Using the Census data and Ministry of Health reports, I wanted to understand more deeply about Luuka district and its pressing issues: Luuka district is one of the 112 districts located in the eastern region of Uganda. According to the 2018 census data, Luuka district is projected to have 262,100 individuals residing and a continued increase in population. However, Luuka district is struggling with high child mortality rates and high maternal mortality ratios. Recent reports show that less than 30% of pregnant women are attending antenatal care 4th visits, and only 13.4% of the population is within 5km proximity to any health facility.

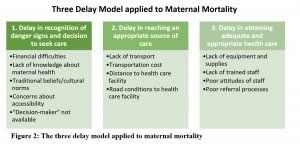

Simply from looking at the Census and Ministry of Health reports, it was clear that Thaddeus and Maine’s three common delays in accessing quality maternal care was applicable to Uganda’s cause of maternal mortality: 1) delay in recognition of danger signs and decision to seek care; 2) delay in reaching an appropriate source of care; 3) delay in obtaining adequate and appropriate health care. The implications and application of the three delay model along with the VASA reports are depicted below by the categories of delay (Figure 1).

Delay 1: Delay in recognition of danger signs and decision to seek care

Along with the COMONETH field workers, including Betty, Rogers, Richard, Susan, and Ester, I visited Luuka district to observe the field workers collect VASA reports from recent maternal and newborn deaths. Following Rogers inquiring into a recent maternal death, we spoke to a caregiver of a deceased mother to understand in depth what happened in the view of the mother and caregiver. From the previous VASA reports and today’s interview, most mothers were not prepared to give birth: no transportation available, no finance to pay healthcare bills or transportation, and the lack of “decision-maker” available.

Often caregivers exclaimed that they spend an average of at least 5 hours to make the decision to seek care. They allocate their time in selling assets, such as livestock, to obtain money, requesting for boda boda drivers in the middle of the night, and sometimes even waiting at home until the “decision-maker” (i.e. the one who makes the final decision and initiative; most often this is the husband of the mother) is available. Every factor further delays the actual transportation to a health care facility and receiving adequate and appropriate care. In addition, many mothers and caregivers are not educated to detect the danger signs and pertinent positive symptoms.

As one of COMONETH’s project components, the research team has deployed Village Health Teams (VHT), a type of voluntary community health workers, to increase the community mobilization and preventive care. VHTs visit the mothers during pregnancy and after pregnancy to educate the mothers and caregivers of danger signs, prenatal care, birth preparedness, immunization and vaccination. Through these interventions, many mothers and caregivers testified the decrease in mortality rates by increasing their readiness for birth and possible complications.

Delay 2: Delay in reaching an appropriate source of care

As I walk through the roads from Betty’s house to the Makerere University’s office, the roads are packed with hustling and bustling boda bodas, a local motorcycle taxi, and trucks with stashes of produce. Unfortunately, the roads for these transportations are extremely poor and dangerous. Not only do these roads have numerous potholes, but also difficult to enforce road regulations: speed limit, helmets, limit of number of individuals on a boda boda. With the increase in young, reckless boda boda drivers, the roads are full of drivers speeding through the potholes and bumps, barely missing a severe accident from occurring. Despite the danger, most caretakers and mothers reported using boda bodas to visit clinics and health facilities to deliver their child or to receive urgent care.

Could you imagine the mothers in labor, severe abdominal pain, or extreme vaginal bleeding on these boda bodas?

To better understand the distances of health care facilities, using Google MyMaps feature, I made a map marking every health facility that we visited and drove by in Luuka District. Note that Health Centers (HC) II acts as an outpatient clinic to treat common diseases like a cold consisting with enrolled nurse and midwives, HC III acts as a general outpatient clinic and a maternity ward with a lab led by a senior clinical officer, and HC IV acts as a mini hospital with a theatre to carry out emergency operations such as birth delivery and delivery complications. HC IV is, ideally, where the mothers should have their birth delivered. The line and circle branching around HC IV represents 5km radius from the facility.

With poor road conditions and far distances to the health care facility, most mothers have no choice other than to deliver their newborn home or at a traditional birth attendant’s (TBA) home. Moreover, analyzing the VASA reports, caregivers report that most mothers were either found dead at home, en route, or on arrival to a health care facility.

In order to decrease the burden of this delay, COMONETH deployed videos and documentaries of mothers and caregivers testifying the importance of birth readiness. During one of the field visits, a mother reported to us since the VHTs and community health workers have been deployed with maternal educational videos, all of her children are all alive and healthy. To further spread the impact, the COMONETH team is in the process of creating a documentary of the mothers and caregivers telling their success stories.

Delay 3: Delay in obtaining adequate and appropriate health care

Analyzing the causes of maternal mortality through VASA, I noticed another common determinant of maternal mortality: most deceased mothers experienced poor provider care, insufficient or lack of supplies and service, delay in care, and negligence of providers. Many caretakers of the deceased reported that they were often referred to multiple clinics and facilities due to lack of blood for transfusion.

Referral processes are another barrier in care for the mothers as most mothers and caregivers report seeing multiple providers before seeing an actual doctor at HC IV. More often, mothers don’t even reach HC IV due to the time wasted in proper referrals. Many mothers initially see a TBA which often aggravate the mother’s and newborn’s conditions, and by the time they reach an adequate and appropriate health care facility, there is nothing the providers can do.

The COMONETH team has been addressing this issue by ensuring consistent health care to the mothers and infants; in 2012, Luuka district had total of 28 functional health facilities and, in 2018, has increased to 38 functional facilities. The COMONETH team also has partnered with Dr. Felix, resident doctor working at HC IV, to increase surveillance levels of maternal and newborn mortality as well as serving healthcare services for the community.

We also visited the Chief Administrative Officer (CAO), presenting the work done over the course of the last 3 years and suggestions after the project ends in the next few months. We addressed the health budget allocation, the importance of continuing VHTs and community health workers, and necessity to eliminate traditional birth attendants. I also had the chance to directly report to CAO the need of sustainable healthcare for the community and increase of staff to provide quality service.

Through this internship, I was given an opportunity to understand the vitality of social determinants of health and strengths of verbal and social autopsies. COMONETH’s work has truly addressed the foundations of health such as importance of health education, health facilities qualities and provider care, which are interventions that are not only sustainable but also causes a positive ripple effect to the community.

This was particularly a meaningful experience for me as this was my first step into maternal and child health research. Moreover, every skill and knowledge such as analyzing the social determinants of maternal health, will advocate my goal as I hope to improve care for women and children in low-resource settings by evaluating the cause and effects to communities’ health and proposing strategies and plans to improve health from the foundation.

*The author is a Master of Science student in Global Health and Population and Child Protection at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Email: janellakang@hsph.harvard.edu